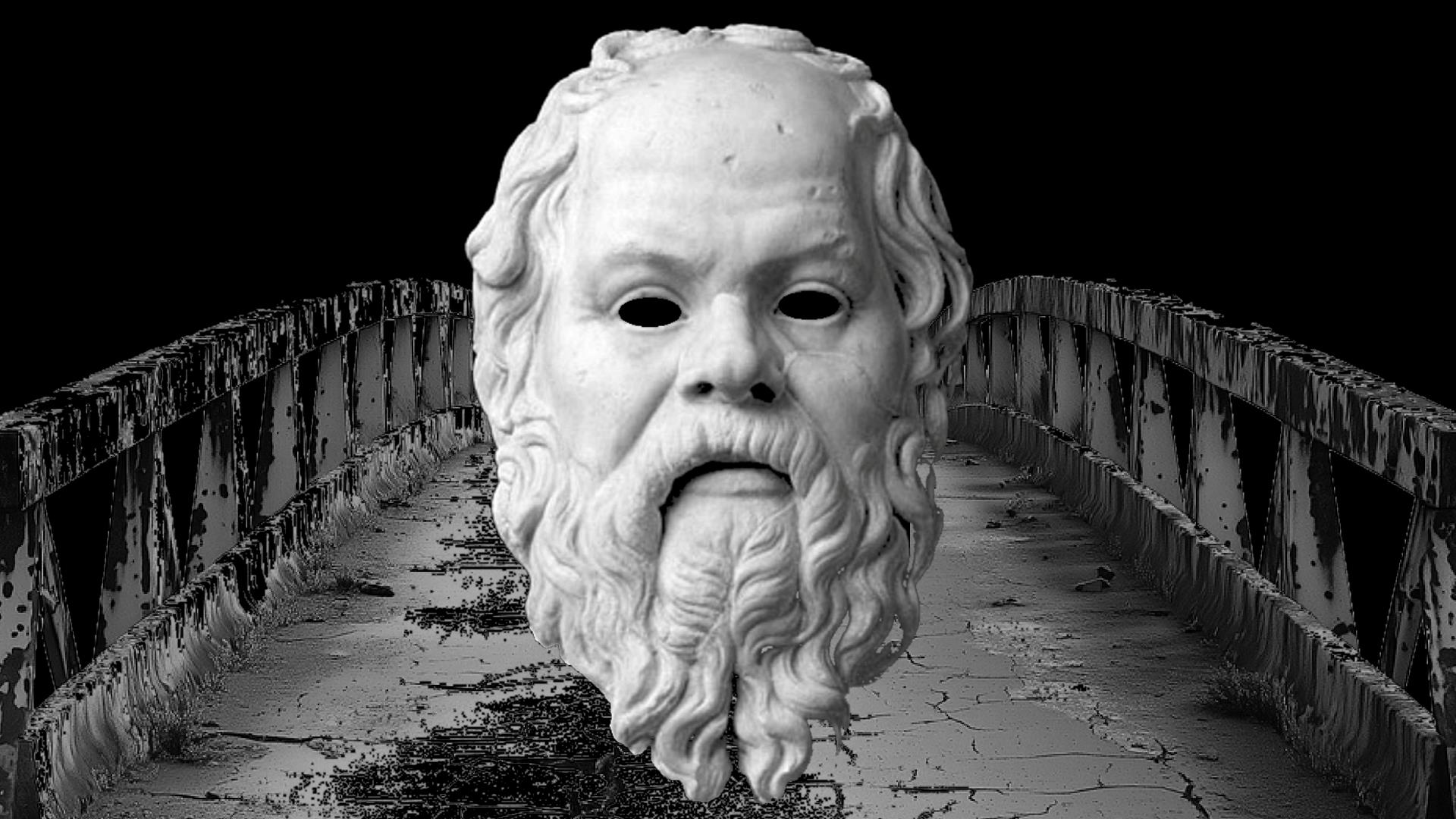

“Death is a decaying bridge no man would cross of his own accord; unless he has made himself ready by embracing his two-edged sword. He casts aside the looming shadows his grasping heart conceives, and finds himself alone at last, from whence emerged his crimson eve.” – Philosopher Muse (An invitation to the Trial and Death of Socrates)

The Trial and Death of Socrates, as depicted in Plato’s dialogues, remains one of the most profound meditations on philosophy, justice, and mortality. Yet, beyond its classical roots, Socrates’ final journey—his trial, imprisonment, and execution—emerges as a powerful dramatization of the dissolution of selfhood and the erosion of societal institutions. In an age marked by political upheaval and cultural uncertainty, Socrates’ existential predicament eerily mirrors the spiritual and political unraveling of contemporary America.

—

Socrates’ ordeal begins with his prosecution by the citizens of Athens, a city he devoted his life to questioning and improving. Charged with impiety and corrupting the youth, Socrates becomes a scapegoat for a society grappling with its own anxieties and failures. His trial is less a search for truth than a demonstration of how democratic institutions—when corrupted by fear, ignorance, and demagogy—can betray their foundational ideals. Socrates stands as the last bulwark against the decline of civic virtue, refusing to capitulate to the mob’s demands or abandon his philosophical principles.

—

This drama of institutional collapse is not foreign to the American experience. The United States, founded on ideals of liberty, reason, and justice, now faces its own moment of reckoning. Political polarization, the erosion of public trust, and the rise of misinformation mirror the Athenian malaise that led to Socrates’ condemnation. Just as Athens, wounded by war and social strife, sought easy answers in scapegoating, America finds itself susceptible to similar temptations—vilifying dissenting voices and forsaking the difficult work of self-examination.

—

Socrates’ imprisonment further dramatizes the fragmentation of selfhood. Stripped of his public role and faced with imminent death, Socrates confronts the limits of his individual existence and the fleeting shape of personality. In the dialogues, he wrestles not only with the injustice of his sentence but also with the ultimate questions of identity and meaning. Is there a self that endures beyond the destruction of the body and the silencing of the voice? Socrates’ refusal to escape, even when offered an opportunity, is not mere stubbornness. It is a testament to his belief in the unity of self and principle: to flee would be to betray himself, to dismantle the very character and identity that has sustained him.

—

This existential upheaval resonates in contemporary America, a nation beset by spiritual dislocation. The decline of shared narratives, the weakening of communal bonds, and the spread of alienation all contribute to a sense of unraveling. The question Socrates faces—how to remain whole in a world that fragments—becomes the question of every American who feels lost amid the desolation of meaning and purpose.

—

The philosopher’s descent into hell is both an individual and collective ordeal. Socrates both gladly and willingly drinks the hemlock, fully aware that his death is not just the end of a man, but a sign of the times; i.e., the decline of democracy. Nevertheless, he dies with dignity all the same, continuing to urge all to care for their souls and that of society. This final act is no defeat but a call to renewal—a recognition that the unraveling of selfhood and society can only be countered by courage, consideration, and an unwavering commitment to truth, even if it means losing everything, including our lives.

—

Here’s the link to my artistic vision of The Trial and Death of Socrates: