“Less you drink of my cup you are not worthy of my wine. No man can be brave as he walks thro’ the passage of time; if unable to lay down his life for the best in mankind.”

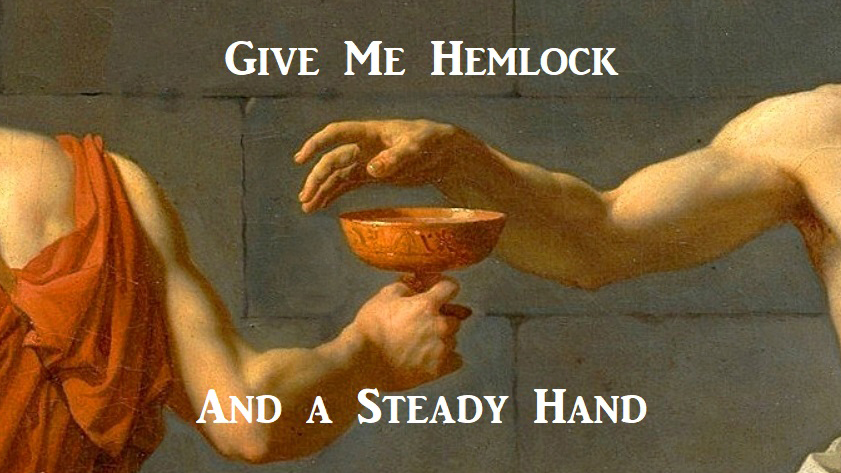

Meletus may have demanded the death penalty, but it was Socrates who forced the hand of the Athenian court to sentence him to die by voluntary death. He chose the hemlock as he chose his words — deliberately, calmly, and with good reason. If the act of taking one’s own life were inherently wrong, we can rest assured that the philosopher of old would have refused the cup. The same can be said of the young man who asked for his cup to be removed in the Garden of Gethsemane, yet drank of it all the same—a story of another kind, and perhaps for another time.

—

On the contrary, Socrates embraced the long night of his own accord, without the oversight of healthcare professionals. Had he been unable to carry out the act due to sickness, weakness, or incapacity, it would have been perfectly acceptable for his companions to assist in his agency. Whereas the notion that specially trained medical professionals needed to supervise Socrates’ passing would have been absurd, unnecessary, and, quite frankly, a waste of city funds.

—

Socrates did not meet his end in submission to the will of others, but through a conscious act of reason — a final affirmation of the philosopher’s duty to live, and die, by principle rather than bureaucratic prescription. His death was not a medical procedure but a moral sovereignty, freely chosen in full awareness of its meaning. It was, in essence, philosophy lived to its last breath. Though separated by millennia, the philosopher’s cup and the physician’s syringe invite the same question: what does it mean to die well, and by whose authority is that dignity conferred?

—

Although our practices surrounding death have changed over the centuries, the underlying moral dilemma persists. This enduring debate has now shifted into the realm of clinical oversight, where the right to die is primarily regulated as a privilege under the purview of technocratic authorities. As a result, what was traditionally grounded in individual conscience and courage has been reconstituted as a procedural system, one in which compassion requires official sanction and personal autonomy is contingent upon compliance. Thus, the discussion moves beyond the question of whether death should be dignified—an issue Socrates arguably resolved—to a more pressing concern: has the very concept of dignity become contingent on state authorization?

—

MAID serves an important purpose for those who need medical assistance, but why should it be the only sanctioned path? Some argue that exclusive medical oversight ensures safety and ethical safeguards, thus protecting vulnerable individuals from coercion or hasty decisions. However, this perspective raises the question: must we delegate our final exit to administrative caretakers, even when safe, self-reliant alternatives exist? What of those capable of choosing their own manner of departure—must they always find their way barred by medical gatekeepers, as if personal agency were insufficient without institutional validation?

—

This shift toward a state-sanctioned monopoly on mortality reveals a deeper, more unsettling irony: in our pursuit of “safety and comfort,” we have sanitized the exit at the expense of the individual’s agency. By insisting that a dignified death can only occur within the sterile confines of a clinical protocol, we imply that the citizen is no longer capable of navigating their own finality. MAID should remain available to those who need it, but making it the sole legitimate option would be a grave mistake.

—

Alas, we have replaced the philosopher’s cup with a medical checklist, ensuring that every departure creates enough red tape to reach the North Pole. If the only ‘safe’ exit is through the State, then dying is no longer an act of genuine freedom; it is a surrender to a design that elevates mechanistic compliance over personal character, procedure over autonomy. For those who are competent and capable, self-reliance ought to remain a dignified choice!

—

Give me hemlock and a steady hand; better to depart by one’s own command.

Grant me only that which is truly mine; justice and liberty until the end of time.