Know thyself: these were the two words inscribed on the entrance to the Oracle of Delphi. Philosophia begins with this injunction—and so Plotinus begins where we all must necessarily begin: with oneself. Who am I? What am I? Human experience contains many different facets: bodily sensation, emotion, conscious and subconscious thought, memory, intuition, and more. Which of these aspects are more essential, and which are more peripheral? Can we establish a meaningful priority among these manifold aspects of the self? (Click here to listen to this post being read-aloud by yours truly.)

—

In a sense, Plotinus reimagines the primary question, asking instead: where am I? That is, where exactly do we ‘locate’ consciousness, ontologically speaking? Through empirical investigation, we know that consciousness is centred within the brain—but this is a purely extrinsic explanation. Plotinus, by contrast, wishes to pinpoint the unique quality of the intrinsic human experience in order to gain inner clarity regarding our relationship to ourselves and to the world around us. In short, Plotinus’ begins by drawing his ontological map with an arrow indicating, ‘You are here.’

—

Plotinus calls our intrinsic experience of consciousness psuche, which we usually translate as ‘soul’. We should be careful to understand Plotinus’ use of this word however. The meaning of ‘the soul’ has been filtered through centuries of theological and philosophical interpretations which we today often unknowingly assume: the individual soul as a Cartesian ego, or as some kind of vague, ghostly, ether substance, etc. As we go further on in the Enneads, what the word Soul means for Plotinus will become clearer. For the moment, however, it is best to sweep aside as much as possible all these inherited notions of ‘the soul’ and to imagine Soul not so much a What as it is a Where in the bigger picture of Plotinus’ ontological map.

—

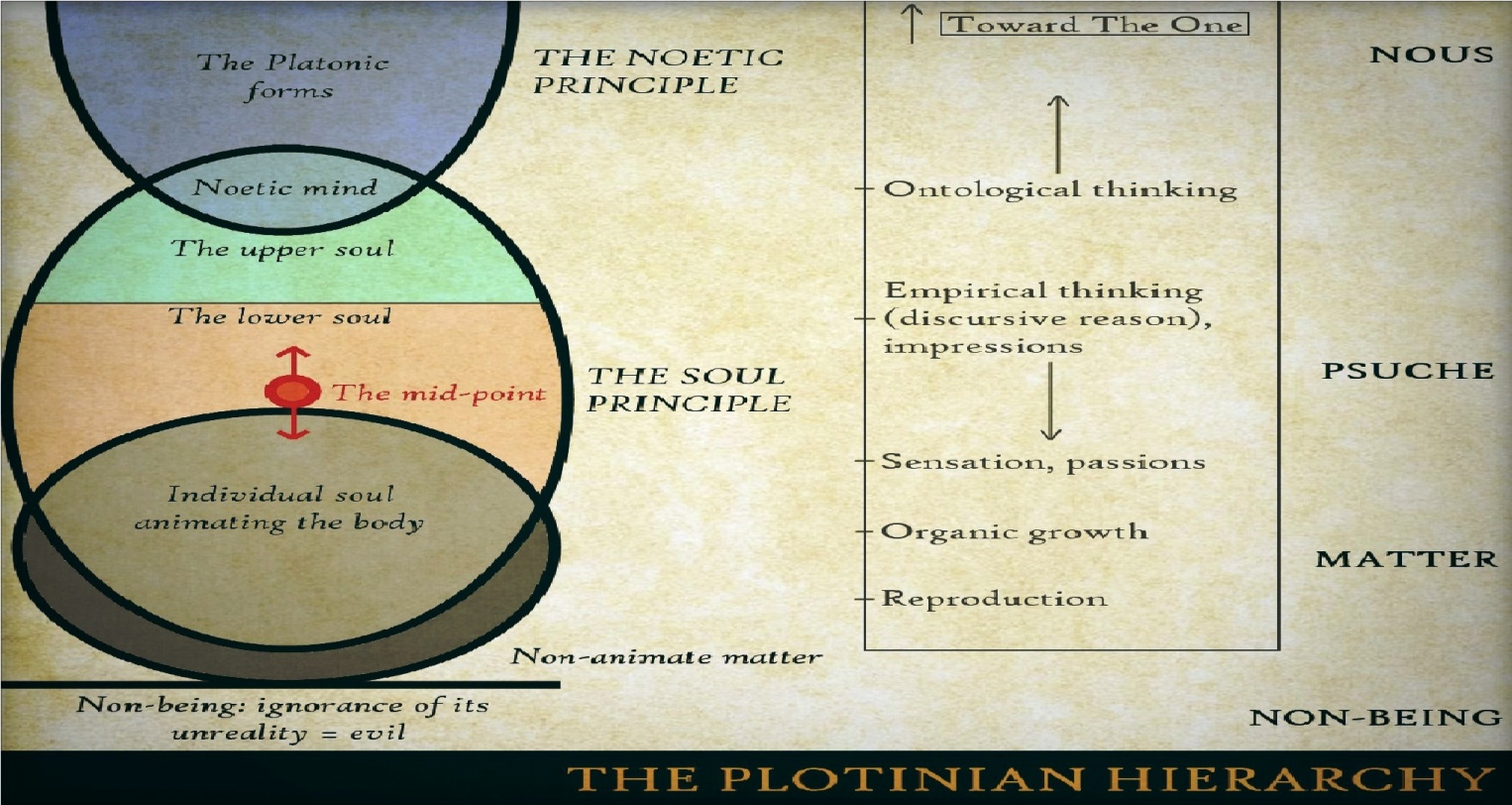

For Plotinus it is a given that Soul is not to be centrally identified with the material body itself. Yet it is undeniable that there is some sort of relation between Soul and body [I.1.1]. How does Soul and body interact? Where do our various kinds of human experiences arise? Plotinus offers three schematic alternatives: [1] within Soul alone, disconnected from the body, or [2] in some kind of combination of Soul and body, or [3] something entirely other than Soul or body (Figure 1):

Plotinus applies these same three alternatives in relation to our experience of sensations, affections, discursive reason, etc. After a cursory examination of these three possibilities {I.1.1-3], Plotinus opts for structure number [2], which indicates an overlapping of Soul and body [I.1.3], but which also, crucially, shows a significant degree of independence of the two. It is in this sense that Plotinus speaks of a ‘lower’ part of Soul and a ‘higher’ part, which correspond to that part of Soul which overlaps with the animate body (the lower) and that which is independent of body (the higher). With this model in mind, we can now more clearly locate, ontologically, where sensation, emotions, thought, and so on, properly reside.

—

This overlapping of Soul and body reveals a key principle to understanding Plotinus’ thought, guiding his entire philosophy: the principle of participation. The One, which binds all of reality into one integral whole, emanates downward through all the levels of being, ‘producing’ the world by virtue of its ontological unity. In this way, Plotinus’ model is hierarchical, comprised of higher and lower levels of Being. Each level exists in relation to the one next to it, below and above. Each successive step lower in the Plotinian hierarchy participates in the step directly above it.

—

And it is at this point that we may recognise Plotinus’ divergence from the common modern (Christian and post-Christian) Western notion of the individual soul—that is, generally identifying it with something like a Cartesian ego. At first Plotinus seems easy enough to understand—we have an individual soul which is at least partially ‘in’ the body. But Plotinus goes further still. We each possess a particular, individuated soul only insofar as it is connected directly to body. Plotinus states that there is an ‘undivided Soul’ and ‘that Soul which is divided among [living] bodies’, and uses a startling image of Soul being divided among different bodies, ‘like one face caught by many mirrors’ [I.1.8].

—

It is not so much that we each possess individual souls in the plural, but rather that body, insofar as it is animated, participates in Soul. Thus body only appears to create partitions within Soul, thus creating our experience of individual souls, separate consciousnesses. Looked at from this perspective, we can then depict this relationship as follows (Figure 2):

On the level of matter (the empirical world), there are individual bodies. Each animated body participates in the ontological level above it, which is Soul. Thus, insofar as each living body participates on the level of soul, soul in body consequently perceives itself as being an entity separate from all other human beings. In other words, individual personality occurs within the lower soul, due to what Plotinus calls ‘the Couplement’ of Soul and body.

—

The perception of the separate ego is only due to Soul ‘looking downward’ so to speak, toward body, with its own particular limited perspectives—limited, that is, by space and time. Body and soul, insofar as they overlap, are conditioned by culture, history, personal dispositions, individual experiences, and a unique spatio-temporal perspective. It is in this lower part of soul which we can identify with the human personality or ego. We appear to be limited, bound consciousnesses, but this occurs to us only by ‘looking through’ the narrow, material ‘partitions’ of the body. Soul is not bound in the same way that body is.

—

It is for this reason that Plotinus states that the tareas of philosophia is “to direct this lower Soul towards the higher, the agent, and except in so far as the conjunction [of Soul and body] is absolutely necessary, to sever the agent from the instrument, the body…” [I.1.3] This direction upward—the ontological orientation of the individual soul—is the primary focus of the philosophical life.

—

It is important to note the too-often overlooked qualification that Plotinus makes in his thought, as shown, for example, in this passage. Note that Plotinus states ‘except in so far as the conjunction is absolutely necessary…’ Asceticism certainly plays a role in the Enneads, but hardly an unhealthy, world-denying self-flagellation. Plotinus aim is not to deny the necessary existence of the material world, only to deny its ontological priority. This is the meaning of Plotinus’ hierarchy: each level of being indeed does have its place—the problem lies in our failure to recognise their ordering. With our ontological priorities mixed up, disintegration is sure to follow, whereas a proper alignment will gradually lead to the integration of the human being.

—

Now we may expand our map which Plotinus verbally describes. The Couplement of Soul and body gives the human being life—this is the realm of the lower soul. Lower still is the animated body itself. This body, as long as animated by soul, is the domain of the most basic biological functions (in common with other forms of life): reproduction, bodily functions pertaining to organic growth, and sensation. The lower soul, in conjunction with body, is the domain of affections as we generally experience them in the world, and, higher still, discursive reason, which also calculates in various ways things in the world (Fig 3):

Plotinus generally links the affections with the lower soul (with body) and not the upper soul (separate from body) because the body is indeed linked to physiological responses to our emotions, such as physical desire [I.1.5]. By the same token, the desire for the Good belongs higher, to the upper soul alone and thus ‘the impulse toward the Good cannot be a joint affection, but, like certain others too, it would belong necessarily to the Soul alone.’ Where such affections belong depends on the ontological orientation of the individual soul. Facing downward, desire may be carnal—facing upward, desire is transposed higher, urged to seek something above Soul rather than below it.

—

This impulse upward leads to the next level of being above Soul—which Plotinus calls in Greek Nous, or as we shall translate here, Noetic Mind, to which we will examine more closely later. The higher soul is the domain of noetic reason (as opposed to discursive reason), which connects Soul to the level of Noetic Mind: And towards Noetic Mind what is our relation? By this I mean, not that faculty in the soul which is one of the emanations from Noetic mind [i.e. noetic reason], but Noetic Mind itself. “This also we possess as the summit of our being….” [I.1.8] Whereas the lower soul overlaps (or ‘spills’ into) matter, the upper soul is overlapped (or ‘spilled’ into) by Noetic Mind. These are the lower and upper boundaries of the individual soul itself (Figure 4):

Plotinus then takes a look back downward within the individual soul again [I.1.9]. If the ontological orientation upward leads toward greater integration and wholeness, then the orientation downward leads to disintegration and fragmentation. This is what Plotinus means by the word ‘evil’—which we should understand in an ontological sense. Or rather, for Plotinus, ethics is framed ontologically: if the Good represents absolute integration, unity and simplicity (being the One), then ‘evil’ indicates absolute disintegration, disunity, and unbound and chaotic multiplicity.

—

What leads toward disintegration is faulty reason directed entirely downward. Rather than reason properly guiding one’s life, highest priority is placed upon the affections, sensation, and other lower aspects of the bodily life—everything is topsy turvy, disordered. We mistakenly place ourselves at the mercy of our changing desires and aversions according to various circumstances we encounter. To repeat: affections, sensations, growth, and reproduction in the human life do have their place—but if we follow any of them blindly instead of guiding ourselves by reason, then our priorities get out of order: “When we have done evil it is because we have been worsted by our baser side—for a man is many—by desire or rage or some evil image: the misnamed reasoning that takes up with the false, in reality fancy, has not stayed for the judgement of the Reasoning-Principle: we have acted at the call of the less worthy…” [I.1.9] Rather than be dictated by these lower aspects of ourselves—which distort our capacity to think clearly—we should cultivate greater contact with our ability to reason.

—

Plotinus places emphasis upon one basic choice which each individual may make. Actually, it is not so much a choice as it is an awareness of the Good within oneself, and recognising our desire for it, and kindling this spark, no matter how faint it may seem. Thus the commencement of the philosophical life depends upon what Plotinus calls the mid-point of the soul: ‘[O]ur entire nature is not ours at all times but only as we direct the mid-point upwards or downwards….’ [I.1.11] In short, the journey towards integration hinges upon one’s own overall ontological orientation.

—

Continuing to address the intersection of ethics and the cultivation of the ontological orientation, Plotinus then explains where in the individual soul that ‘sin’ arises {I.1.12]. The word ‘sin’ here in the Greek is hamartia, meaning ‘fault’, ‘error’—or, more literally, ‘missing the mark’. The word was originally used in reference to the downfall of heroes in Greek tragedy, lacking the more judgemental, moralistic overtones that accumulated in the Christian use of the term. Plotinus states that fault lies in the lower soul, whereas the upper soul, not limited by body remains free from it. What this means is that fault arises in the human personality (where the Couplement takes place), but the higher soul remains untouched by it. The crucial question however, is: are we aware of that higher soul? As long as the ontological orientation faces downward, this higher soul does not become ‘activated’ so to speak.

—

It is not really that body is the source of fault but that the lower soul takes on an ‘alien accruement’ which begins at birth. Birth is synonymous with ‘a descent of the soul’ into body. Soul becomes habituated to body and identifies too readily with it. This is what the alien accruement signifies, and it distorts self-perception due to an almost perpetual ontological orientation downward. Consequently, we invest ourselves less in reason for guidance as we do the satisfaction of the body or the lower soul, seeking pleasure, wealth, power, fame—often at the expense of reason. It becomes our emotions which guide us instead of reason, particularly anger, fear, or desire, which distort our perception of the world, easily leading to all kinds of vice. From this ethical perspective, Plotinus and the Stoics coincide generally speaking.

—

And so, to return to the original question: Who am I? Or rather, where am I? Plotinus ends here by returning to this point [I.1.13]. The self is Soul, not body. That is, consciousness takes place at an ontologically higher level than that of the material, empirical world. But what complicates matters is that the lower soul and body overlap. Through virtue, Soul may learn to cease its false identifications with the body, as well as distortions arising in the Couplement. This is necessary in order for Soul to recognise its own true identity and place, orienting itself toward that which is higher, toward the level of Noetic Mind. This is done through noesis, or noetic thinking, an ontologically-based thought-activity in Soul which urges ever-upward. Insofar as Soul participated in Noetic Mind, we are capable of noetic thinking, while Noetic Mind simultaneously draws ourselves upward. Thus it is through noetic thinking that Soul transcends itself, up into Noetic Mind.